How Tehran Wields Power in Iraq, Secret Documents

- 2019-11-18 10:59:07

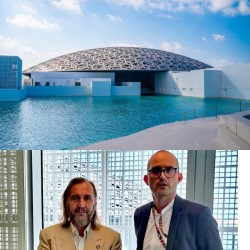

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Al-Alimi to Meet Saudi Defense Minister Over Hadramout and Al-Mahra Developments

Al-Alimi to Meet Saudi Defense Minister Over Hadramout and Al-Mahra Developments Muslim Brotherhood Leader Threatens to Strike the White House

Muslim Brotherhood Leader Threatens to Strike the White House Government Recovers Bodies of 20 Fighters in Tribal-Mediated Exchange with Houthis in Marib

Government Recovers Bodies of 20 Fighters in Tribal-Mediated Exchange with Houthis in Marib Racist and antisemitic false information spreads online following Bondi Beach terrorism attack

Racist and antisemitic false information spreads online following Bondi Beach terrorism attack Shabwa Governor Orders Swift Legal Action Over Unlawful Tribal Execution That Shocked Yemen

Shabwa Governor Orders Swift Legal Action Over Unlawful Tribal Execution That Shocked Yemen