Lebanon protests escalate as currency dives

- 2020-06-12 14:16:01

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Two US soldiers, one interpreter killed in ISIS ambush in Syria

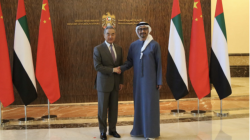

Two US soldiers, one interpreter killed in ISIS ambush in Syria China to enhance strategic mutual trust, advance cooperation with UAE

China to enhance strategic mutual trust, advance cooperation with UAE Israel targets senior Hamas official in deadly Gaza strike

Israel targets senior Hamas official in deadly Gaza strike Authorities respond to reports of rainwater inside Grand Egyptian Museum

Authorities respond to reports of rainwater inside Grand Egyptian Museum Yemen : ACJ Urges UN to Replace Houthi Representatives in Muscat Negotiations

Yemen : ACJ Urges UN to Replace Houthi Representatives in Muscat Negotiations