When the virus came to our hospital

- 2020-08-20 09:50:18

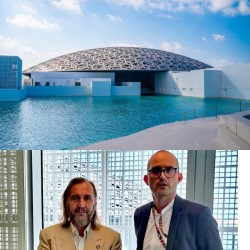

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital UAE announces full withdrawal of its forces from Yemen

UAE announces full withdrawal of its forces from Yemen UAE reaffirms commitment to de-escalation in Yemen

UAE reaffirms commitment to de-escalation in Yemen Yemen’s STC announces two-year transitional phase

Yemen’s STC announces two-year transitional phase Yemen: Seven Saudi Airstrikes Hit STC in Camp in Hadramout, Casualties Reported

Yemen: Seven Saudi Airstrikes Hit STC in Camp in Hadramout, Casualties Reported Yemen: Faces Critical Phase Amid Rising Security Concerns in Red Sea

Yemen: Faces Critical Phase Amid Rising Security Concerns in Red Sea