Afghan-Taliban peace talks: What's next?

- 2020-09-23 07:52:26

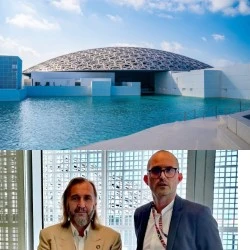

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change UAE Humanitarian Initiative Provides Clean Water to Thousands in Northern Gaza"

UAE Humanitarian Initiative Provides Clean Water to Thousands in Northern Gaza" Terrorists Kill Eleven Police Officers in Burkina Faso

Terrorists Kill Eleven Police Officers in Burkina Faso Mubadala targets opportunities in AI and robotics, CEO says

Mubadala targets opportunities in AI and robotics, CEO says Air Force One Forces Trump To Delay Davos Trip

Air Force One Forces Trump To Delay Davos Trip UAE contributes $5 M to support humanitarian response in Sudan

UAE contributes $5 M to support humanitarian response in Sudan