The assassination of a ‘Brave Journalist of Afghanistan’

- 2020-11-23 10:35:11

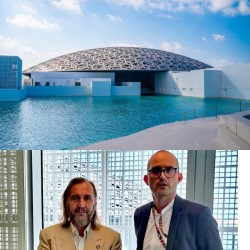

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital UAE Expresses Solidarity with Libya and Conveys Condolences over Army Chief's Plane Crash

UAE Expresses Solidarity with Libya and Conveys Condolences over Army Chief's Plane Crash 3 former Assad officials killed in clashes with state forces in Alawite area of Syria

3 former Assad officials killed in clashes with state forces in Alawite area of Syria UK Welcomes UNSC Statement on Yemen, Urges Houthis to Release Detained UN Staff

UK Welcomes UNSC Statement on Yemen, Urges Houthis to Release Detained UN Staff Greek Among Victims of Jet Crash in Turkey Carrying Libyan Army Chief

Greek Among Victims of Jet Crash in Turkey Carrying Libyan Army Chief ADQ closes $5bln financing deal with Asian financial institutions

ADQ closes $5bln financing deal with Asian financial institutions