Waldemar Haffkine: The vaccine pioneer the world forgot

- 2020-12-11 21:25:48

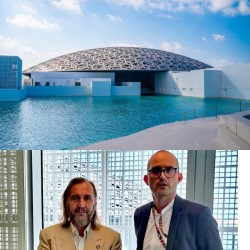

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital ADNOC Gas and EMSTEEL Sign $4bln, 20-year natural gas supply agreement to power UAE’s industrial growth

ADNOC Gas and EMSTEEL Sign $4bln, 20-year natural gas supply agreement to power UAE’s industrial growth Joint Statement by UK, France Condemns Houthi Actions in Yemen

Joint Statement by UK, France Condemns Houthi Actions in Yemen Jordan Security Forces Kill Two Extremist Fugitives in Ramtha

Jordan Security Forces Kill Two Extremist Fugitives in Ramtha Maersk to Resume Shipping Through Red Sea and Bab al-Mandeb After Months of Houthi Threats

Maersk to Resume Shipping Through Red Sea and Bab al-Mandeb After Months of Houthi Threats 3 Arrested in Paris Suspected of Spying and Acting for Russia

3 Arrested in Paris Suspected of Spying and Acting for Russia