The disease-resistant patients exposing Covid-19's weak spots

- 2021-02-23 10:56:56

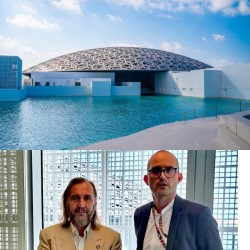

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital UAE Welcomes Statements by U.S. Secretary of State on Sudan and the Cessation of Hostilities

UAE Welcomes Statements by U.S. Secretary of State on Sudan and the Cessation of Hostilities Netanyahu to present Trump with new Iran attack plans during US visit

Netanyahu to present Trump with new Iran attack plans during US visit CAF institutes AFCON every 4 years and League of Nations

CAF institutes AFCON every 4 years and League of Nations 51 Yemeni Fishermen Return to Mocha Port After Release from Eritrea

51 Yemeni Fishermen Return to Mocha Port After Release from Eritrea EU Announces Success of "ASPIDES" Naval Mission Securing Passage of 1,400 Commercial Vessels in the Red Sea

EU Announces Success of "ASPIDES" Naval Mission Securing Passage of 1,400 Commercial Vessels in the Red Sea