John F Kennedy: When the US president met Africa's independence heroes

- 2021-02-27 16:54:08

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Egypt, Foreign Ministry: ‘Italian woman dies in collision between two cruise boats on the Nile’

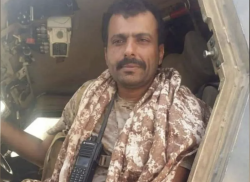

Egypt, Foreign Ministry: ‘Italian woman dies in collision between two cruise boats on the Nile’ Yemeni Commander Survives Roadside Bomb Attack in Shabwa

Yemeni Commander Survives Roadside Bomb Attack in Shabwa Germany Issued Over 100,000 Family Reunion Visas in 2025 Despite Stricter Measures

Germany Issued Over 100,000 Family Reunion Visas in 2025 Despite Stricter Measures Yemen : Security Forces in Al-Dhalea Seize Truck Suspected of Carrying War-Material Bound for Houthis

Yemen : Security Forces in Al-Dhalea Seize Truck Suspected of Carrying War-Material Bound for Houthis Gas Stations Reopen in Yemen's Taiz After Price Increase

Gas Stations Reopen in Yemen's Taiz After Price Increase