The midwives braving armed gangs in Colombia

- 2021-03-01 14:31:42

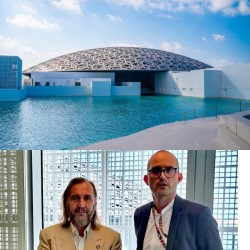

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Joint Statement at Conclusion of HRH the Crown Prince’s Visit to the United States

Joint Statement at Conclusion of HRH the Crown Prince’s Visit to the United States Sudan welcomes US and Saudi mediation efforts to end civil war

Sudan welcomes US and Saudi mediation efforts to end civil war Cristiano Ronaldo thanks Trump after White House dinner amid Saudi-US ties

Cristiano Ronaldo thanks Trump after White House dinner amid Saudi-US ties WHO Announces Arrival of New Measles Vaccine Shipment for Yemeni Children, Funded by Saudi Arabia

WHO Announces Arrival of New Measles Vaccine Shipment for Yemeni Children, Funded by Saudi Arabia Saudi PIF, SITE, Microsoft sign MOU to explore delivery of sovereign-cloud services in kingdom

Saudi PIF, SITE, Microsoft sign MOU to explore delivery of sovereign-cloud services in kingdom