Can Trump's Syria policy end the 'Forever Wars'?

- 2019-01-13 19:13:49

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Washington Urges Sudan’s Warring Parties to Accept Immediate Ceasefire

Washington Urges Sudan’s Warring Parties to Accept Immediate Ceasefire UAE Urges Civilian Transition in Sudan, Warns of Regional Spillover

UAE Urges Civilian Transition in Sudan, Warns of Regional Spillover Syria and Kurdish-led SDF agree to de-escalate after deadly clashes in Aleppo

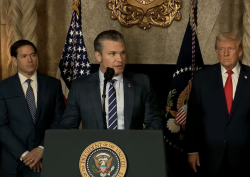

Syria and Kurdish-led SDF agree to de-escalate after deadly clashes in Aleppo Trump Announces New Class of Battleship

Trump Announces New Class of Battleship Gargash: UAE Works with Partners for a Stable, Prosperous Region Free of Extremism

Gargash: UAE Works with Partners for a Stable, Prosperous Region Free of Extremism