Coronavirus: New York becomes Ground Zero again

- 2020-05-02 17:24:17

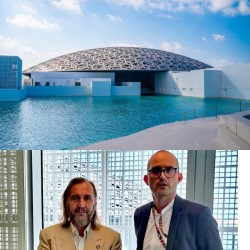

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital EU Reaffirms Commitment to Yemen’s Unity, Urges De-escalation

EU Reaffirms Commitment to Yemen’s Unity, Urges De-escalation Syria says ISIS leader captured in joint operation in Damascus countryside

Syria says ISIS leader captured in joint operation in Damascus countryside New York Times: UN Staff Held by Houthis in Yemen Excluded from Upcoming Exchange Deals

New York Times: UN Staff Held by Houthis in Yemen Excluded from Upcoming Exchange Deals Jordanian army strikes near Sweida after intercepting arms, drugs smugglers near border

Jordanian army strikes near Sweida after intercepting arms, drugs smugglers near border UAE Expresses Solidarity with Libya and Conveys Condolences over Army Chief's Plane Crash

UAE Expresses Solidarity with Libya and Conveys Condolences over Army Chief's Plane Crash