Hong Kong extradition: How radical youth forced the government's hand

- 2019-06-17 21:51:15

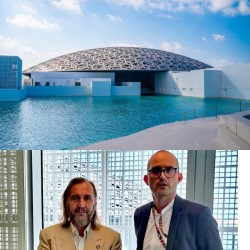

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital ACJ Condemns Extrajudicial Execution in Shabwa, Yemen

ACJ Condemns Extrajudicial Execution in Shabwa, Yemen Morocco Advance to the FIFA Arab Cup Final With Win Over the United Arab Emirates

Morocco Advance to the FIFA Arab Cup Final With Win Over the United Arab Emirates PM Netanyahu Meets with US Ambassador to Turkey and Special Envoy to Syria Tom Barrack

PM Netanyahu Meets with US Ambassador to Turkey and Special Envoy to Syria Tom Barrack Death toll from floods rises to 37 in western Morocco

Death toll from floods rises to 37 in western Morocco AD Ports to launch tender offer for majority stake in Alexandria Container Handling

AD Ports to launch tender offer for majority stake in Alexandria Container Handling