Young Iraqis and Lebanese aren't just demanding better societies. They're creating them at protest sites

- 2019-11-07 17:06:58

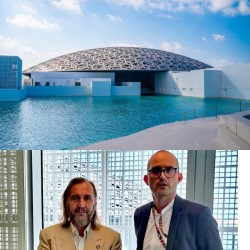

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Washington Welcomes Saudi and Emirati Support for Yemen’s Sovereignty, Regional Security

Washington Welcomes Saudi and Emirati Support for Yemen’s Sovereignty, Regional Security Trump team reportedly 'frustrated' with Netanyahu over fears he would undermine peace process

Trump team reportedly 'frustrated' with Netanyahu over fears he would undermine peace process France: 3 women stabbed in Paris metro, suspect arrested

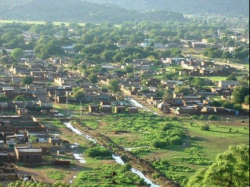

France: 3 women stabbed in Paris metro, suspect arrested Airstrike in Sudan’s Kordofan Kills and Injures 31 Civilians During Christmas Celebrations

Airstrike in Sudan’s Kordofan Kills and Injures 31 Civilians During Christmas Celebrations UAE, Pakistani leaders discuss expanding economic, energy ties in Islamabad meeting

UAE, Pakistani leaders discuss expanding economic, energy ties in Islamabad meeting