Discovering WW1 tunnel of death hidden in France for a century

- 2021-03-15 15:14:24

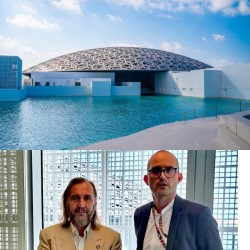

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Israel army strikes 4 towns in southern Lebanon after evacuation orders

Israel army strikes 4 towns in southern Lebanon after evacuation orders UNSC to Hold Mid-Month Meeting on Yemen

UNSC to Hold Mid-Month Meeting on Yemen Doctor jailed for supplying ketamine to ‘Friends’ star Matthew Perry

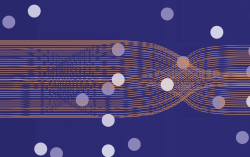

Doctor jailed for supplying ketamine to ‘Friends’ star Matthew Perry UAE bids to sweep Africa into its AI industrial revolution

UAE bids to sweep Africa into its AI industrial revolution Al-Qaeda in Yemen Confirms Death of Senior Leader Abu al-Haija al-Hadidi

Al-Qaeda in Yemen Confirms Death of Senior Leader Abu al-Haija al-Hadidi