The Hong Kong crisis and the new world order

- 2020-07-03 14:44:05

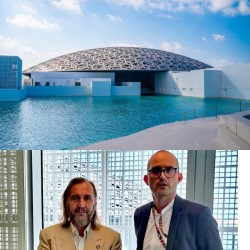

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi

Pierre Rayer: Art, Science, and Happiness: The Universal Mission of Transmission to Future Generations through Patronage at the Louvre Abu Dhabi Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC

Ahly crowned Super champions after dramatic extra-time win over Modern Future FC Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change

Yemeni Honey..A Development Wealth Threatened By Conflict And Climate Change California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut

California wildfires: Millions warned of possible power cut Central African rebels launch attacks near capital

Central African rebels launch attacks near capital Morocco vs Senegal: Fans Speak Ahead of AFCON 2025 Final

Morocco vs Senegal: Fans Speak Ahead of AFCON 2025 Final Abu Dhabi Bids Farewell to Former Southern President Ali Salem al-Beidh

Abu Dhabi Bids Farewell to Former Southern President Ali Salem al-Beidh Iraq takes full control of air base after US withdrawal, defense ministry says

Iraq takes full control of air base after US withdrawal, defense ministry says AFCON final - Morocco seek to overcome Senegal to seal symbolic victory after decades of investment

AFCON final - Morocco seek to overcome Senegal to seal symbolic victory after decades of investment King Receives Invitation from Trump to Join Peace Council

King Receives Invitation from Trump to Join Peace Council